The search for the proverbial fountain of youth is moving underwater. Experimental biologist Itamar Harel, returning to Israel this spring from a post-doc at Stanford University School of Medicine, will establish an aging research lab focused on the tiny East African turquoise killifish, the shortest-lived vertebrate that can be cultivated in the laboratory easily.

Gleaning insights into human aging from a fish that lives an average of four to six months sounds counterintuitive. But the East African turquoise killifish has an aging progression remarkably similar to ours, making it perfect for studying human aging in a rapid timeframe.

“In the past 25 years, experiments in short-lived yeast, worms and flies have revolutionized the way we perceive aging – revealing that the aging rate itself can be manipulated by genetic and environmental interventions,” Harel says.

“However, the lack of short-lived vertebrate models for genetic studies has significantly limited our understanding of vertebrate aging, including the role of vertebrate-specific genes, organs and physiological processes.” At Stanford’s Brunet Lab, Harel used a new genome-editing technique called CRISPR to develop a tool for examining aging and disease in killifish.

Harel’s own lab, to open in March 2018 at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Institute of Life Sciences, will take this research to the next level.

“The key aspect I’m trying to accomplish is to see if we can slow down some of the age-associated diseases we have and extend good health, even if we live the same amount of years,” Harel tells ISRAEL21c.

“I envision using killifish as a platform for testing the role of specific drugs and their effect on age-associated pathologies such as cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases,” he says.

“Manipulating the aging rate itself might allow us to postpone the onset of these devastating diseases, which will have a tremendous impact on human health.”

The 37-year-old scientist got his undergraduate degree at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in 2005 and his PhD in developmental biology at the Weizmann Institute of Science in 2012.

When he arrived at Stanford in 2013, he was fascinated to learn about the killifish, which has been bred in captivity since 1968 but had never been genetically engineered.

The tool he developed using CRISPR enabled him to study the effects of early interventions on elderly killifish.

“I was able to do it almost twice as fast as in parallel genetic models like mice, which have a lifespan of two to three years,” he says. In his Jerusalem lab, he will study aspects of aging unique to vertebrates.

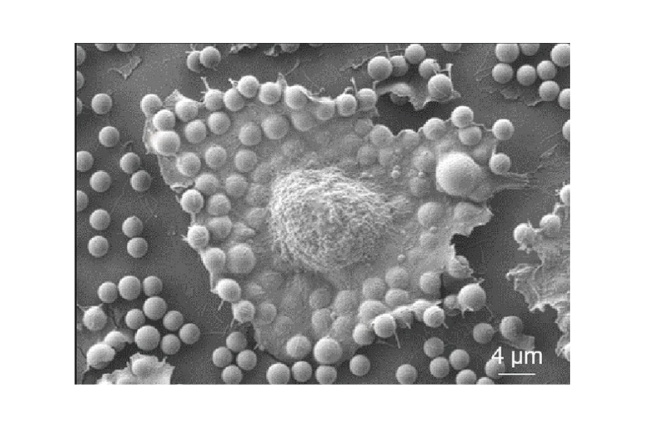

“The majority of aging research has been done on invertebrates, in which it is challenging to study things like bone degeneration, declining immune function, declining ability to benefit from vaccinations, and increasing susceptibility to cancer and infections,” says Harel.

“I think my uniqueness will be to study specific niches that are exceptionally challenging or impossible to study using current models.”

To start, Harel will investigate dyskeratosis congenita syndrome, which causes bone-marrow failure.

“The killifish model shows rapid onset of this disease and I want to see if we can develop interventions to slow down some of these phenotypes, screen for drugs and do genetic interventions.”

People have studied this syndrome in mice but you have to breed them for three to four generations before the phenotypes develop.

In killifish, the phenotype happens in the first generation, and as fast as only two months.” In the long term, Harel hopes the little fish will reveal why aging is the primary risk factor for every disease type. “We know different organisms live vastly different lifespans.

Killifish live six months, while koi fish live up to 200 years,” he says.

“Nature has fabulously played with this trait of the aging rate. If we understand the basics behind the differences we could potentially manipulate them ourselves and see what aspects make the body more susceptible or more resilient.” He isn’t trying to make killifish live as long as koi fish.

“But we could tailor specific interventions to boost our ability to cope with Alzheimer’s or other degenerative diseases,” says Harel, whose family history does not include any centenarians that he knows of. Harel notes that aging research is advanced in Israel, with multiple aging-related research labs doing groundbreaking work.

The Israeli Ministry of Science and Technology recently issued a call for “technologies and innovation for older persons,” including biomedical research on aging.

In October, Israeli longevity expert Dr. Nir Barzilai from Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York gave a keynote address, “How to die young at a very old age,” at the Pathways to Healthy Longevity conference at Bar-Ilan University sponsored in part by the Israeli Longevity Alliance.

Harel was on the judging panel that awarded prizes to graduate students studying the biology of aging, healthy longevity and quality of life.

“Doing research in Israel comes with a sense of community and ease of developing new collaborations,” says Harel. “For me it was clear that I wanted to go back.”