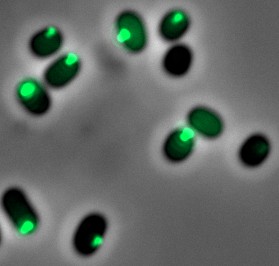

As much of the world debates how to address marijuana use, the vast majority of American states have legalized it or allow it for medical purposes. Global pharmaceutical companies and hospitals seeking effective treatments using cannabis should look to Professor Raphael Mechoulam, a scientist at Hebrew University. Mechoulam, a pioneer in the field, was the first to isolate, analyze and synthesize the major psychoactive and non-psychoactive compounds in cannabis and has developed a number of revolutionary marijuana-related treatments.

Today, roughly 147 million people use medical marijuana for effective relief of various ailments, including AIDS, multiple sclerosis, Crohn’s disease, cancer treatment side effects and Parkinson’s. Experts believe these numbers will grow exponentially in the coming years, and Mechoulam is now widely recognized as the godfather of medical marijuana, the high priest of his field.

Mechoulam began studying marijuana as a young professor in 1964. He learned that researchers had isolated morphine from opium over 150 years ago and cocaine from coca leaves a century prior, yet no one had tried to understand cannabis and its psychoactive and non-psychoactive ingredients. Mechoulam and his colleagues became their own test subjects and after a few months not only understood marijuana’s ingredients, but found a way to test its medicinal properties.

Not long after Mechoulam’s human experiments with THC, the major psychoactive compound in cannabis, he applied for a grant with the US National Institutes of Health, but the response was not exactly welcoming. “Cannabis is not important to us,” he recalls an NIH official telling him. “When you have something relevant, call us… marijuana is not an American problem.” At the time, not a single US lab was working on it.

In 1965, the NIH changed its tune at the insistence of a member of Congress, who was concerned about his son’s recreational use. Mechoulam had just isolated THC for the first time and discovered its structure. Dan Efron, head of pharmacology at the National Institute of Mental Health, promised Mechoulam financial support for further research. In return, the professor sent the NIH the entire world supply of synthesized THC, about 10 grams, which the NIH used to conduct many of the original cannabis experiments in the United States.

Today, thanks to Mechoulam’s research over the past half century, doctors around the world prescribe marijuana for a variety of disorders. Mechoulam’s work catapulted Israel to the top of the field of medical marijuana testing.

“Israel is the marijuana research capital of the world,” says Dr. Sanjay Gupta, chief medical correspondent for the Health, Medical & Wellness unit at CNN.

Globally, there is an obstacle to wider acceptance of medical marijuana: doctors themselves. Mechoulam believes that use of the drug is not standard practice because most physicians are not yet familiar with it and because most doctors are uncomfortable with a medicine that can be consumed by inhaling its smoke. But Mechoulam has played a major role in dispelling misconceptions about cannabis.

“The problem is that for many years, marijuana was put on the [same] scale as cocaine and morphine,” Mechoulam says. “This is not fair. All drugs, starting from aspirin to valium, [have] side effects. One has to know how to use them.”

Until recently, pharmaceutical companies weren’t enthusiastic about applied research on the drug. The legal ambiguity around cannabis and the difficulty of filing patents on a plant that has existed forever limit their ability to make money.

“It is still widely believed that cannabinoids are drugs and they make you crazy, make you mad, that they don’t have therapeutic value and they are addictive,” says Manuel Guzman, a professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at Complutense University in Madrid and one of the world’s leading scientists studying the effects of cannabis on cancer cells. But, according to Guzman, that’s “based on ignorance. Knowledge takes time to get absorbed by society and the clinical community.”

At the federal level, cannabis is still illegal in the United States, which prevents serious and ongoing research on THC and on CBD, the non-psychoactive compound in cannabis. But 23 states and the District of Columbia have legalized marijuana for some medical uses, and according to polling data, a majority of Americans now favor legalization for recreational purposes. Elsewhere in the world, there is even more momentum. Israel, Canada and the Netherlands all have medical marijuana programs. Uruguay has legalized pot and Portugal has decriminalized the drug.

All of this gives reason for optimism about the future of medical marijuana research, according to Mechoulam, who is now investigating the drug’s effects on asthma. It is clear that his groundbreaking life’s work and “never, ever give up” attitude are slowly changing the minds of his peers. “If a Nobel Prize was given on cannabis research,” Dr. Guzman says, “Rafi would be the leading candidate.”

The writer is the author of Thou Shalt Innovate: How Israeli Ingenuity Repairs the World (Gefen Publishing) and a senior fellow at the American Foreign Policy Council.