The human race spends a great deal of time fighting the inevitable. Just about every stage of life is inevitable, but we exercise to live longer, eat certain diets to stay healthier, and undergo treatments and use different products to ‘stay younger.’

As it pertains to that last one, an interesting new study indicates that perhaps we are right to be concerned, and if anything, our concerns should start sooner than they already do.

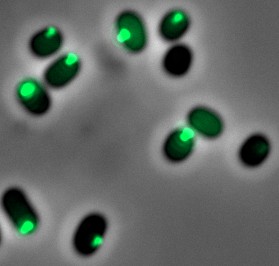

Through the use of separation of young and old yeast cells, which can cycle through a full generation in about four hours, Dr. Yaakov Nahmias at Hebrew University in Jerusalem was able to demonstrate that the ability to remove malformed proteins diminishes as yeast ages.

What does it all mean? According to Dr. Nahmias, founding director of the Alexander Grass Center for Bioengineering at Hebrew University the study implies that signs of aging could occur in humans as early as the onset of puberty.

Of course, most organisms are thought to decline in the later stages of the aging process, and that’s certainly the thought process taken by most humans. But as the study points out, there are two aspects of aging in yeast: chronological and replicative aging. Chronological aging corresponds to the life span of a non-dividing cell, while replicative aging corresponds to the number of cell divisions that an individual yeast cell goes through.

Results suggest that protein quality control is affected in early stages of replicative aging, which would explain the predictive signs observed earlier in life.

Proteins are at the heart of most aging-related discussions these days, as researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison recently discovered mice making a surplus of a human protein called AT-1 show signs of early aging and premature death, which are also symptoms of the human disorder progeria.

By restoring a cellular function in these mice, the researchers were able to reverse the aging signs and prevent the premature deaths of these mice.

Along with clues about the biological pathways causing progeria, the findings may shed light on other developmental and aging-related disorders. Variations in the AT-1 gene have been linked to several health conditions, including autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disabilities and increased risk of seizures, among others.

“The AT-1 protein is involved in a host of quality-control processes in our cells that affect both development and aging,” says Luigi Puglielli, senior author of the new study and a professor in UW–Madison School of Medicine and Public Health and the Waisman Center. “We have taken key steps toward uncovering the biology of this protein.”

Puglielli clarified that he’s not discussing reversing aging; rather, the ability to perhaps delays the onset of age-related conditions by years or even decades, and thus extending the quality of life for people well into the future.