Every year in the United States, more than 35,000 people die and 2.8 million get sick from antibiotic-resistant infections. Now, a team led by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HU)’s Professor Nathalie Balaban and Shaarei Zedek Medical Center’s Dr. Maskit Bar-Meir, has shown that resilient bacteria may be treatable with currently-available therapies. In a study published in Science magazine, the researchers show that aggressive bacteria can be controlled – but only if doctors administer treatment within a short window of opportunity.

Like all living organisms, germs like bacteria develop defenses against hostile elements in their environment. One common tactic is “tolerance,” that is, lying dormant during antibiotic treatment. In this way, bacteria evade antibiotic treatment because antibiotics can only spot and kill growing targets. However, this intermediary stage called “antibiotic tolerance” lasts only a few days and cannot be detected in standard medical labs. Therefore, doctors miss the tolerance window and with it the opportunity to treat a serious infection before it becomes altogether resistant. This short window does not affect most healthy adults but for those patients fighting off a blood infection with a weakened immune system, this window is critical and could mean the difference between life and death.

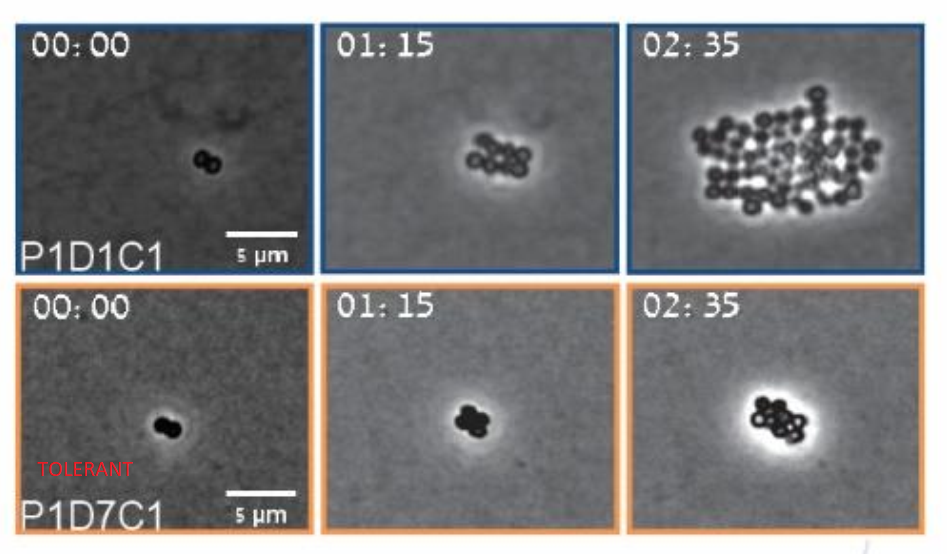

Credit: Nathalie Balaban and Jiafeng Liu.

In a previous study, Balaban and Ph.D. student Irit Levin-Reisman studied lab-controlled bacteria. They developed a mathematical model that successfully described, measured, and predicted when bacteria would develop tolerance to a particular antibiotic. Further, they observed that when bacteria developed tolerance to one antibiotic, they were more likely to develop tolerance to other antibiotics in the cocktail. “We observed that bacteria acquired tolerance within a few days. These tolerance mutations then acted as a stepping stone to acquire resistance and, ultimately, treatment failure,” described Balaban.

Now, as published in the latest edition of Science, HU’s Balaban lab and Dr. Jiafeng Liu teamed up with Bar-Meir and repeated their study and tolerance test technique. Only this time, they analyzed daily bacterial samples from hospitalized patients with life-threatening, persistent MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) infections. The pattern that they found was strikingly similar to their lab findings: First, the patients’ bacteria developed tolerance, then resistance, and ultimately antibiotic treatment failed.

Looking ahead, Balaban believes that the same evolutionary processes involved in the development of antibiotic tolerance and resistance are likely at play in cancer and might be used to inform treatment. For example, tumor cells might first become tolerant of chemotherapy, develop resistance to it, and then develop resistance to other cancer drugs, as well.

Credit: Hebrew University

In the short term, Balaban and Bar-Meir would like to give new hope for patients with life-threatening infections by encouraging medical centers to adopt the laboratory test they developed which gauges antibiotic tolerance. This readout would enable doctors to quickly and easily detect whether a patient’s bacteria are tolerant of a planned antibiotic treatment before it’s administered. Further, based on the patient’s bacteria profile, doctors could handpick antibiotics with a greater chance of success that, as is currently done, blindly choose antibiotics for which the patient may have already developed a tolerance. “Using the right combination of available antibiotic drugs at the outset could dramatically increase a patients’ survival rate before their infection becomes tolerant to all the antibiotics in our arsenal,” Balaban concluded.

###

CITATION: Effect of tolerance on the evolution of antibiotic resistance under drug combinations. Liu Jiafeng, Orit Gefen, Irine Ronin, Maskit Bar-Meir, and Nathalie Q. Balaban. Science, January 10, 2020. Vol. 367, Issue 6474, pp. 200-204. DOI: 10.1126/science.aay3041

FUNDING: European Research Council, Israel Science Foundation, Minerva Foundation.