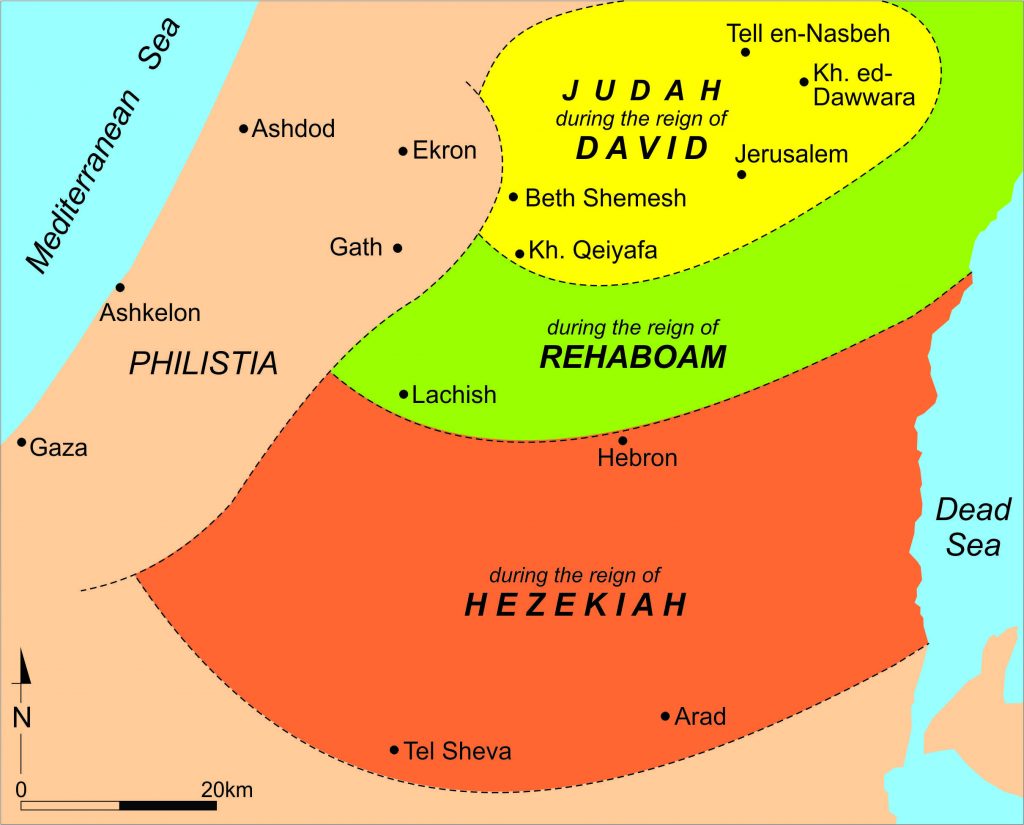

July 10, 2023—The Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology recently published an article written by Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HU) Prof. Yosef Garfinkel, the Yigael Yadin Chair in Archaeology of Israel. The article, titled “Early City Planning in the Kingdom of Judah: Khirbet Qeiyafa, Beth Shemesh 4, Tell en-Naṣbeh, Khirbet ed-Dawwara, and Lachish V,” discusses the comprehensive study led by Prof. Garfinkel, in which he examines the earliest fortified sites in the kingdom of Judah during the 10th century BCE. The research focuses on five key sites: Khirbet Qeiyafa, Beth Shemesh, Tell en-Naṣbeh, Khirbet ed-Dawwara, and Lachish. These sites reveal significant insights into the urbanization process, urban planning, and establishing the borders of the earliest phase of the kingdom of Judah in the days of King David and his grandson, Rehoboam. The Shephelah (shefela) region, located southwest of Jerusalem, played a crucial role in the kingdom of Judah’s development due to its favorable ecological conditions for agriculture. The research highlights Shephelah’s low rolling topography, fertile soil, and ample precipitation as factors that made it the breadbasket of the kingdom and a region capable of supporting a large population. The study emphasizes the importance of the kingdom’s expansion into the Shephelah region and its agricultural resources as a key stage in its development. Contrary to previous beliefs that the kingdom’s expansion occurred in the late 9th or 8th century BCE, 200 to 300 hundred years after David, Prof. Garfinkel’s research demonstrates that the kingdom had already begun expanding into the hill country and the northern Shephelah region as early as the 10th century BCE. The southern Shephelah expansion followed approximately two generations later in the time of Rehoboam.

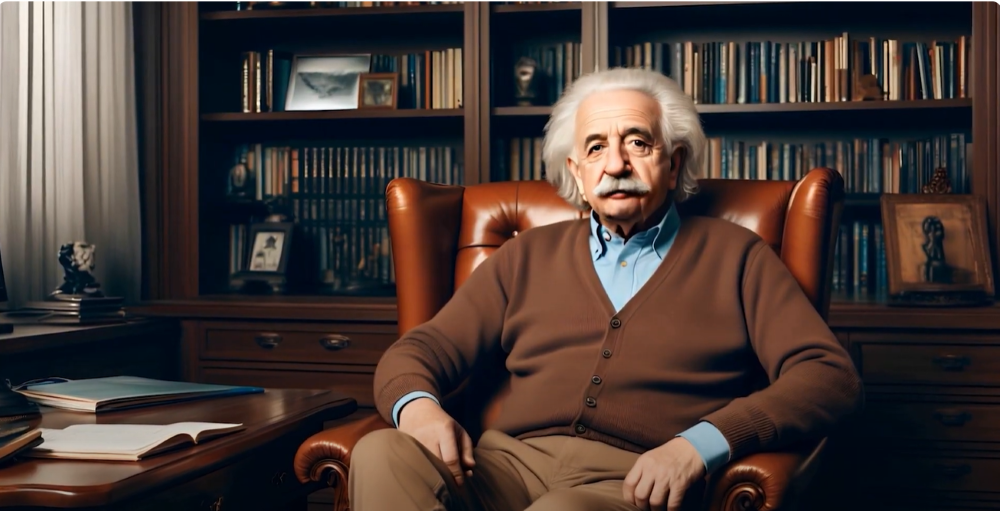

Credit: Yossi Garfinkel

The sites included in the study showcase an urban plan characterized by a casemate city wall (a double wall with transverse walls separating the area between the main walls into chambers) with a peripheral belt of structures abutting the wall, although Lachish, Level V, exhibits a similar pattern but without casemates in its city wall. The findings have far-reaching implications for understanding the urban planning and territorial boundaries of the earliest phase of the kingdom of Judah.

These cities share three characteristics: they were fortified with a casemate city wall (Lachish, Level V being the exception), they are located on the kingdom’s borders, and are situated on a main road leading into the kingdom. Khirbet Qeiyafa in the Elah Valley protected the southwest border of the kingdom. Beth Shemesh in the Soreq Valley protected the western border of the kingdom. Tell en-Naṣbeh near Ramallah protected the North, and Khirbet ed-Dawwara protected the northeast border. Radiometric dating techniques confirm that the fortified cities of Khirbet Qeiyafa and Beth Shemesh date back to the first quarter of the 10th century BCE, the era of King David. The analysis of the urban planning and geographical location of the sites clearly indicates that the kingdom of Judah was a strong kingdom and was able to build well-planned cities on its borders that could protect the main roads leading into its capital, Jerusalem.

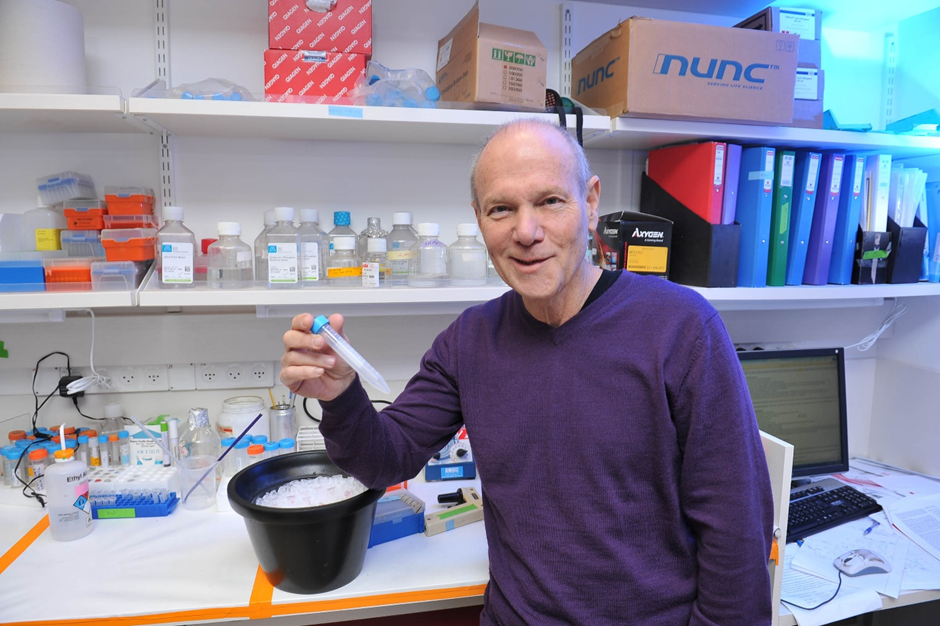

Credit: J. Rosenberg

This research sheds new light on the early city planning of the Kingdom of Judah and enriches our knowledge of the urbanization process and territorial expansion during the 10th century BCE.

Prof. Garfinkel provided an explanation of the research findings, stating, “The discovery of a barrier wall in this area effectively defines the boundaries of the urban core of the Kingdom of David, putting an end to the longstanding historical debate surrounding the existence of the Kingdom and its borders.” He further elaborated, affirming, “This finding provides tangible evidence on the ground, dated to the relevant period, supporting the biblical accounts of King Rehoboam’s expansion and fortification as described in the Book of Chronicles. It is a rare instance where we can present empirical historical and archaeological evidence aligning with biblical narratives from the tenth century BCE.”

Regarding the publication date of the research, Prof. Garfinkel explained, “What was needed was someone to come along and observe the complete picture that these findings portray. I am glad that I was able to fulfill that role.”

The excavations that formed the basis of these conclusions were conducted by Saar Ganor, Inspector for the Israel Antiquities Authority and a lecturer at the Hebrew University, and Prof. Michael Hazel, Professor and Director of the Southern Adventist University (U.S.) Institute of Archaeology.